New Microscopy Works at Extreme Heat, Sheds Light on Alloys for Nuclear Reactors

A new microscopy technique allows researchers to track microstructural changes in real time, even when a material is exposed to extreme heat and stress. Recently, researchers show that a stainless steel alloy called alloy 709 has potential for elevated temperature applications such as nuclear reactor structures.

“Alloy 709 is exceptionally strong and resistant to damage when exposed to high temperatures for long periods of time,” says Afsaneh Rabiei, corresponding author of a paper on the new findings and a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University. “This makes it a promising material for use in next-generation nuclear power plants.

“However, alloy 709 is so new that its performance under high heat and load is yet to be fully understood. And the Department of Energy (DOE) needed to better understand its thermomechanical and structural characteristics in order to determine its viability for use in nuclear reactors.”

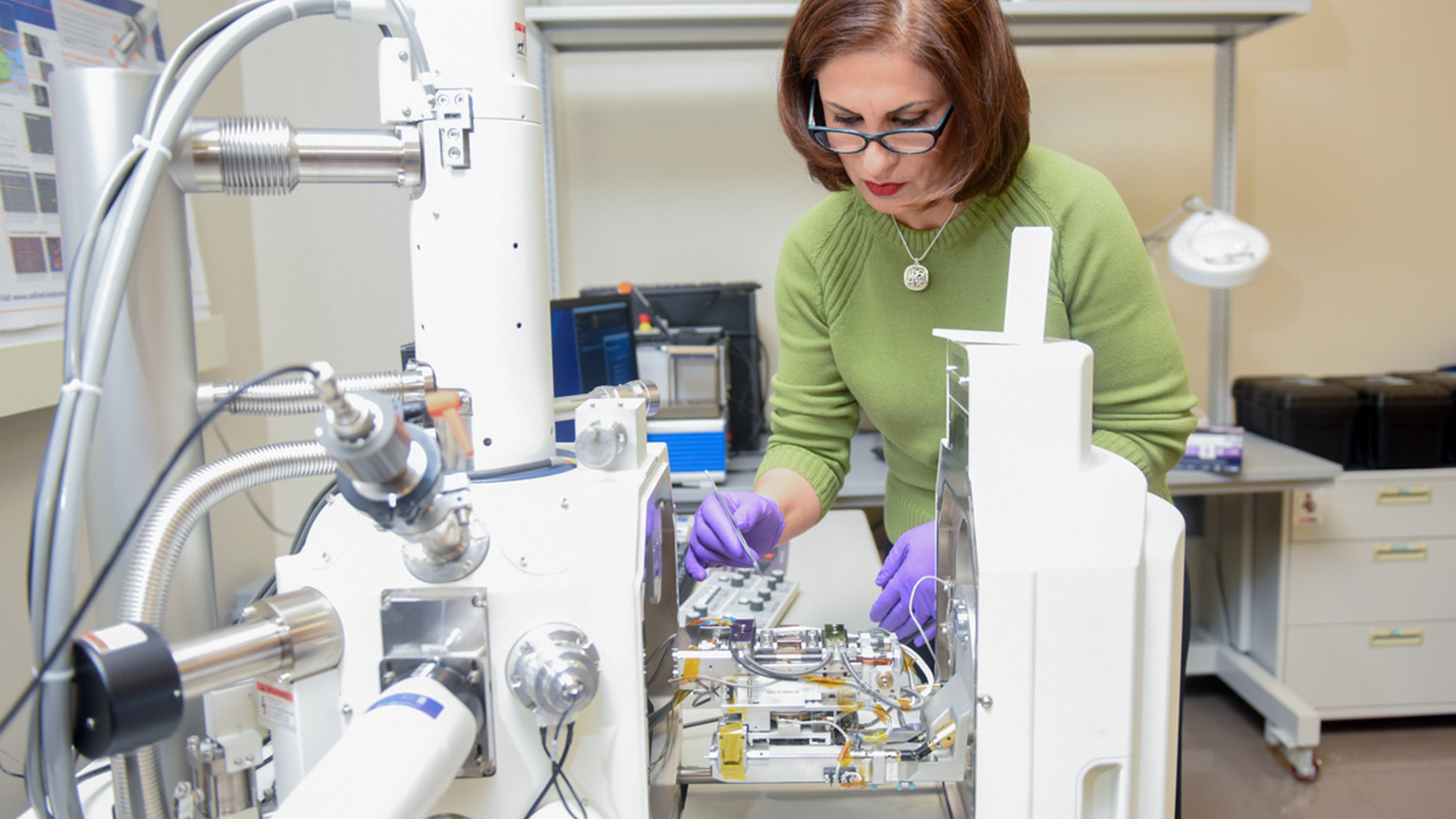

To address DOE’s questions, Rabiei came up with a novel solution. Working with three companies – Hitachi, Oxford Instruments and Kammrath & Weiss GmbH – Rabiei developed a new technique that allows her lab to perform scanning electron microscopy (SEM) in real time while applying extremely high heat and high loads to a material.

“This means we can see the crack growth, damage nucleation and microstructural changes in the material during thermomechanical testing, which are relevant to any host material – not only alloy 709,” Rabiei says. “It can help us understand where and why materials fail under a wide variety of conditions: from room temperature up to 1,000 degrees Celsius (C), and with stresses ranging from zero to two gigapascal.”

To place that in context, 1,000 C is 1,832 degrees Fahrenheit. And two gigapascal is equivalent to 290,075 pounds per square inch.

Rabiei’s team collaborated with the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom to assess the mechanical and microstructural properties of alloy 709 when exposed to high heat and load.

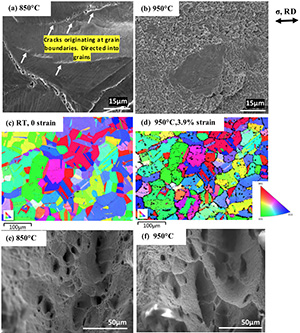

The researchers exposed one-millimeter-thick samples of alloy 709 to temperatures as high as 950 C until the material “failed,” meaning the material broke.

“Alloy 709 outperformed 316 stainless steel, which is what’s currently used in nuclear reactors,” Rabiei says. “The study shows that alloy 709’s strength was higher than that of 316 stainless steel at all temperatures, meaning it could bear more stress before failing. For example, alloy 709 could handle as much stress at 950 C as 316 stainless steel could handle at 538 C.

“And our microscopy technique allowed us to monitor void nucleation and crack growth along with all changes in the microstructure of the material throughout the entire process,” Rabiei says.

“This is a promising finding, but we still have more work to do,” Rabiei says. “Our next step is to assess how alloy 709 will perform at high temperatures when exposed to cyclical loading, or repeated stress.”

The paper, “A Study on Tensile Properties of Alloy 709 at Various Temperatures,” appears in the journal Materials Science and Engineering: A. First author of the paper is Swathi Upadhayay, a former graduate student at NC State. The paper was co-authored by Hangyue Li and Paul Bowen of the University of Birmingham. The work was supported by the Department of Energy under grant number 2015-1877/DE-NE0008451 and by United Kingdom Research and Innovation award number EP/N016351/1.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“A Study on Tensile Properties of Alloy 709 at Various Temperatures”

Authors: Swathi Upadhayay and Afsaneh Rabiei, North Carolina State University; Hangyue Li and Paul Bowen, University of Birmingham

Published: June 23, Materials Science and Engineering: A

DOI: 10.1016/j.msea.2018.06.089

Abstract: In recent years, there have been several advancements in energy production from both fossil fuels and the alternate “clean” sources such as nuclear fission. These advancements are fueled by the need for more efficient systems that will optimize the use of the depleting fossil fuel reserves and shift the focus to cleaner sources of energy. The efficiency of any power generation cycle is dependent on the ability of the structural material to withstand the increased peak operating temperatures. Advanced austenitic stainless steels have been in the focus as structural material for the next generation nuclear power plants, due to their strength, corrosion resistance, weldability and the wide range of temperatures at which the austenitic phase is stable. Alloy 709, a recently developed advanced austenitic stainless steel is being investigated in this paper. In this study, tensile tests were conducted on dog-bone samples of Alloy 709 in an in-situ scanning electron microscope (SEM) loading and heating stage, equipped with electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), at various temperatures. The in-situ experiments indicated that the material primarily accommodated deformation by slip at lower temperatures. Void formation and coalescence at grain boundaries preceded slip at higher temperatures. Although crack initiation at all elevated temperatures was intergranular, the crack propagation through the material and the final fracture was trangranular. Additionally, tensile tests were conducted on larger cylindrical samples at 550, 650 and 750 °C in air. The results of tests conducted in air and in-situ were found to be in agreement, at these temperatures.

- Categories: